A Comparative Analysis of Established and Mass-Produced Lithium-Ion (NMC/NCA) versus LiFePO4 (LFP), versus Sodium-Ion (Na-ion) batteries, on a cell-level basis in cylindrical, prismatic, and pouch cell format. *Please note that this paper excludes any discussion of emerging forms of Lithium Ion, such as Solid-state, semi-solid state, Graphene, etc.

Prepared for: OEMs, System Designers & Integrators, Procurement Teams, and Anyone interested in Learning about Batteries.

| When in pack form, the performance, safety, longevity, and application compatibility of all battery chemistries can vary. This may lead to unexpected results or serious consequences, depending on the engineering, design, and manufacturing skills of the assembly company. Always consult a battery pack assembler with experience in identifying challenges and managing battery production to ensure the desired outcome. |

Foreword

Originally, this was a personal effort. I often get asked about these battery chemistries, and more recently, how Na-ion compares to other widely produced chemistries. I realized I could better address these questions in a whitepaper, so I decided to share it with anyone interested. I hope it is useful and helps clarify a complex topic.

Please consider this paper both as an overview and a summary of the 2025 market and technical reports, including industry reports, major manufacturer announcements, trade press, and recycling studies. It is a compilation of my decades of experience, insights, and trusted industry contacts while also drawing from other industry experts. My goal with this paper is to combine this real-world knowledge with reports and data from across the battery industry spectrum. This makes the document unique in its scope and range of information, providing the reader with valuable insights to make informed decisions about the best battery chemistry for their next project, industry watch, or even targeted investments.

Additionally, for most people, the word “battery” immediately brings to mind EVs. This connection makes sense; however, the battery cells used in modern EVs are physically different and often specially designed for EV applications, making them less suitable for most other uses. Therefore, when we hear about a new factory or breakthrough chemistry, it’s important to understand that it may have little or no relevance to your specific needs outside of the EV world. For example, Toyota’s new factory in North Carolina. While their cells are very exciting for Toyota products and customers, they have little to no impact or value for other companies or applications outside of Toyota.

| About Lithium Power, Inc.: LPI is a leading provider of innovative Lithium and Sodium-ion battery design and manufacturing solutions. LPI is transforming the mobile and portable energy sectors, as well as energy storage, by delivering custom, high-quality, reliable, and safe battery solutions tailored to your specific needs. We are also excited to introduce our latest innovation: ready-made, standardized battery packs available at www.SoluThium.com. With SoluThium, there are no NRE, tooling, or certification costs. Applications include: industrial, medical, autonomous robotics, commercial drones, e-mobility, off-road vehicles, renewable energy storage, and drop-in lead-acid replacement. |

Scope, Sources & Methodology

Giving credit where it is due. My words are based on the trust I place in others to publish accurate statistics and forecasts, and I have compiled everything for you, the reader. I thoroughly researched and curated the publications and articles through standard searches, using some AI, mainly Grok-AI. Knowing where to look and whom to trust is important, and I made an effort to double-check for accuracy and cite all sources.

Primary sources cited throughout include www.MarketsandMarkets.com, industry reports on LFP, CATL/Reuters coverage of sodium-ion activity, and recent recycling and critical minerals analyses (IEA, CAS/industry reviews). Key claims that could change quickly are cited inline. Where possible, market price and adoption figures are referenced to authoritative, recent sources (see citations in the document). The goal is to provide the reader with a practical, procurement-oriented comparison rather than a deep electrochemical primer.

Definition and Overview of each battery chemistry:

*See SWOT for more details on each chemistry

Lithium-Ion

Lithium-ion (NMC/NCA/LCO and other high-energy Lithium-based chemistries). Lithium-ion remains the dominant technology in value and installed capacity in 2025, driven by EVs and portable electronics. This dominance is not expected to change dramatically until at the earliest 2030, as other chemistries or nuances of Lithium-Ion hit critical mass production and adoption. Global Lithium-ion market spectrum — market value projections for 2025 are large (hundreds of billions USD); MarketsandMarkets shows the Lithium-ion battery market projected at roughly ~USD 190–200B in 2025.

- Favored for applications needing a cross-section of cell-types (cylindrical, prismatic, pouch), maximum energy density, high discharge rate capability, good temperature range, and stability of the supply chain, including cost-effectiveness when managed well.

- Challenges: safety (thermal runaway risk), reliance on critical minerals (nickel, cobalt, Lithium), and cost volatility.

- Applications: Conventional Li-ion (NMC/NCA, high-energy): ESS, a wide variety of medical devices, industrial apparatuses, consumer electronics, e-Mobility, UPSs, Data storage, and Mil/Aero applications. Passenger EVs, aerospace, high-energy portable electronics, and some performance EVs.

LiFePO₄ (LFP)

LiFePO₄ (LFP) has rapidly expanded in EVs and stationary storage, and lead acid replacement because of lower cost, improved safety, and long cycle life, wide temperature range, and ever-improving energy density; its share of new EV battery deployments has grown strongly, especially in China and for lower-cost EV models. (Dataintelo) LiFePO₄ (LFP) — LFP adoption accelerated 2022–2025 in EVs (cost-sensitive models), e-bus/commercial fleets, and stationary storage; multiple reports place the LFP segment as one of the fastest-growing chemistry markets in 2025. (LFP market valuations reported in the low tens of billions USD for 2025). (Dataintelo)

- LFP (LiFePO₄) has become the low-cost, safe workhorse for many EVs (especially in China) and stationary storage; cell prices for LFP have fallen to the low-$60/kWh range in recent years. (Reuters)

- Rapidly expanding in EVs and stationary storage due to lower cost, better safety, and long cycle life.

- Made in all cell types – cylindrical, prismatic, and pouch.

- Especially strong in China and cost-sensitive EV markets.

- Lower energy density than NMC, but well-suited where safety and total ownership costs are most important.

- In many cases, repurposing LFP cells and packs is a better proposition than other chemistries.

- Challenges: while safety risk is much lower, it still can go into thermal runaway in certain situations, depending on the cell type and configuration. Reliance on critical minerals (Lithium) and a very limited supply chain outside of China. Recycling is not as cost-effective as Lithium Ion.

- Applications: stationary medical devices, e-Mobility, AMR & AGVs, Truck/RV/Marine applications, and a myriad of applications where lead acid is presently deployed. Stationary energy storage systems (residential to grid), e-buses, commercial fleets, lower-cost EVs, where cycle life and safety / TCO matter more than absolute energy density. Also strong in off-grid solar and industrial backup.

Sodium-Ion (Na-ion)

Sodium-ion is an emerging contender in 2025: major manufacturers (e.g., CATL) moved to pilot and early mass production in 2025, targeting lower-cost stationary and some EV niches where energy density tradeoffs are acceptable. Expect accelerated commercialization 2025–2027. (Reuters)Sodium-ion (Na-ion) — still small in absolute market share in 2025 but fast-growing from pilots to early mass lines; some market forecasts estimate a single-digit % of battery market value by the late 2020s, with 2025 revenues concentrated in consumer power banks, niche EV models, large-small format, and stationary systems. CoherentMarketInsights and other specialized consultancies show multi-billion USD markets emerging by the early 2030s. CATL announced industrial-scale plans in 2025. (Coherent Market Insights)

- Emerging competitor in 2025: pilot and early mass production underway (e.g., CATL Naxtra).

- Strengths: abundant materials, strong safety profile, and potential to be cheaper than LFP at scale. *A key feature is the ability to discharge to zero volts without causing significant cycle life degradation. (See in-depth information in Addendum C.)

- Challenges and limitations: lower energy density, limited recycling infrastructure, and an early stage of commercialization. Limited cell types do not yet allow for a wide range of application adoption. While some supply is outside of NA, such as www.coulombtechnology.com, the vast majority of suppliers remain in China.

- Applications: low-cost stationary storage, consumer power banks, some urban EV segments, and commercial vehicles where weight/volume are less critical but cost and safety are prioritized; edge cases where cold-weather performance and supply security are valuable. CATL planned Na-ion EV packs in 2025, targeting both EV and ESS niches.

Key Takeaways for 2025

- Use high-energy Lithium-ion for premium and range-focused applications.

- Use LFP for mainstream EVs, buses, and energy storage systems.

- Monitor sodium-ion for near-future adoption in low-cost EVs and stationary storage, where density is less critical.

- Supply chain diversification and recycling innovation are strategic imperatives across all chemistries.

Side-by-Side Review of the Unique Attributes of Each Chemistry (Grok-AI)

| Parameter | Lithium-Ion (NMC/NCA) | LiFePO4 (LFP) | Na-ion (Na-ion) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cathode material | Nickel-Manganese-Cobalt or NCA | Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePO4) | Layered oxides (NaNiMnO₂, etc.) or Prussian blue, hard carbon anode |

| Anode material | Graphite | Graphite | Hard carbon |

| Nominal cell voltage | 3.6–3.7 V | 3.2 V | 2.3–3.0 V (typically ~2.5–2.8 V) |

| Specific energy (Wh/kg) | 200–300 Wh/kg (cell level) | 120–180 Wh/kg | 120–200 Wh/kg (current), 200–250+ projected |

| Energy density (Wh/L) | 500–750 Wh/L | 300–450 Wh/L | 250–400 Wh/L (current) |

| Cycle life (80% retention) | 800–2,000 cycles | 3,000–7,000+ cycles | 3,000–8,000+ cycles (some >10,000) |

| Thermal runaway temperature | ~150–200 °C | ~270 °C (much safer) | >300 °C (very safe) |

| Safety | Moderate (can catch fire/explode) | Very high (almost no thermal runaway) | Very high (inherently safer chemistry) |

| Fast charging capability | Good (up to 3–6 C in some cells) | Excellent (commonly 1–3C, some 10C+) | Good to excellent (many support >3C) |

| Low-temperature performance | Poor below 0 °C | Fair (better than NMC) | Excellent (works well down to -30 °C) |

| Cost (2025 estimate) | Highest (~$90–120/kWh pack) | Medium (~$70–90/kWh) | Lowest (potentially <$50/kWh long-term) |

| Raw material availability | Limited (Co, Ni, Li supply constraints) | Abundant (no Co/Ni, Li still needed) | Extremely abundant (Na, Fe, Mn, C) |

| Environmental impact | High (cobalt mining issues) | Lower | Lowest (no rare metals) |

| Current commercial status | Dominant in EVs and consumer devices | Dominant in energy storage & some EVs (Tesla, BYD, etc.) | Early commercialization (CATL, HiNa, Farasis 2024–2025 mass production) |

| Main advantages | Highest energy density | Safety + longevity + cost | Ultra-low cost + abundant materials + safety + Zero Volt capability |

| Main disadvantages | Cost, safety, and resource scarcity | Lower energy density | Lower voltage & energy density (currently) |

| *Best suited for | High-performance EVs, phones, and laptops | Stationary storage, budget/safe EVs | Grid storage, low-cost EVs, and stationary |

See Addendum B for more information about other important market segments.

More About Safety — Comparison & Contrast

Thermal Stability/Fire Risk

- Li-ion (NMC/NCA/LCO, high-energy) — higher energy density but more flammable electrolyte and thermal runaway risk if damaged, overcharged, or poorly managed. Device Incidents and pack-level thermal runaway remain the principal safety concerns, mitigated by pack design, especially thermal management, cell-to-cell propagation management, robust packaging, and masterful BMS design.

- LiFePO₄ (LFP) — significantly better, but not zero thermal/chemical stability than NMC/NCA; much lower tendency to thermal runaway and superior tolerance to abuse (overcharge, high temp). This is why LFP is preferred where safety and cycle life matter.

- Sodium-ion — early 2025 reporting (manufacturer claims, pilot data) indicates sodium-ion packs often have lower fire risk and greater intrinsic safety than NMC chemistries; comparable or slightly better than LFP in some formulations, depending on electrolyte and cell design. However, commercial data at a large scale remains limited. (Reuters)

Operational Temperature & Degradation

- LFP and some sodium chemistries show better low-temperature performance for cycle life and safety margins; high-energy NMC/NCA is still sensitive to temperature extremes and requires more thermal management.

- If temperature extremes are part of the challenge of an application, careful cell selection and seeking out cell makers that specialize in addressing temperature extremes are vital to a safe, robust battery pack.

Conclusion (safety): LFP and Na-ion lead on intrinsic safety; high-energy Lithium-ion trades safety for energy density and must rely more on system controls and pack engineering. *Cost comparison (2025)

Cell/pack Cost Trends:

- Conventional Li-ion (NMC/NCA): pack costs in the low-hundreds USD/kWh range for mainstream EV packs (varying by cell type, scale, and supplier). Continued cost reductions, but constrained by some critical mineral price volatility. (BSLBATT)

- LiFePO₄ (LFP): among the lowest cost per kWh for Lithium chemistries in 2025 due to abundant iron/phosphate feedstocks, simpler cathode manufacturing, and lack of expensive nickel/cobalt. Many OEMs reported TCO advantages for LFP in lower-range EVs and storage. (Dataintelo)

- Sodium-ion: manufacturers and analysts in 2025 projected lower raw-material cost potential than Lithium chemistries (sodium, cheaper anode/cathode precursors). Some quoted future pack-level targets that could undercut LFP with scale (estimates vary widely). Early commercial products were priced competitively in niche markets; mass cost estimates remain forecasted rather than observed at scale. (Bonnen Battery)

- Important caveat: cost numbers vary by geography, cell format, and degree of vertical integration. Public manufacturer roadmaps (e.g., CATL) suggest Na-ion aims to be cost-competitive with or cheaper than LFP at scale. (Reuters)

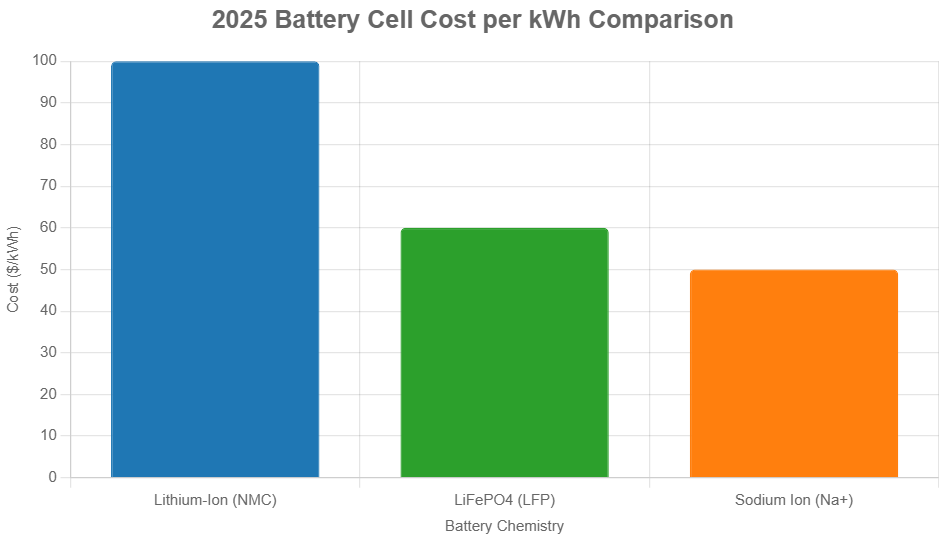

*See Addendum A – chart for the 2025 visualized cost per kilowatt comparison

Manufacturability & supply chain

Raw Material Availability

- Li-ion (NMC/NCA): relies on Lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite, and manganese — several of which (nickel, cobalt, and Lithium) are geopolitically concentrated and face near-term supply/demand tension. IEA and industry reports flag critical minerals as an area of concern. (International Energy Agency)

- LFP: uses iron, phosphate, Lithium (but far less nickel/cobalt). Iron and phosphate are abundant and geographically diversified — easing some supply pressure and enabling broader manufacturing. (Dataintelo)

- Sodium-ion: sodium and many precursor materials are abundant and widely available globally — a strategic advantage for diversified supply chains and cost stability. (Reuters)

Manufacturing Readiness

- Li-ion (NMC/NCA): massive, mature global manufacturing base; high automation and decades of process refinement. Bottlenecks are upstream (active materials, precursor refining) rather than cell assembly. (MarketsandMarkets)

- LFP: well-established cell and pack production lines; many gigafactories retooled or expanded for LFP due to demand. Manufacturing scale-up is straightforward where cell formats are compatible. However, cell manufacturing is highly concentrated in China. Some cell manufacturing is coming online in Indonesia, Taiwan, India, Eastern Europe, and the United States, but all will take several years to have an impact on a global scale. (Dataintelo)

- Sodium-ion: production lines require adaptation but are compatible with existing cell manufacturing infrastructure to a degree. 2025 saw the first industrial lines (CATL Naxtra and others) ramping — manufacturability risk is moderate but improving quickly. (Reuters)

Supply-chain Risks

- Lithium and nickel cobalt exposure remains the highest risk for conventional Li-Ions; LFP and Na-ion provide pathways to diversify away from those pinch points. Trade policy, regional concentration (esp. China for cell production and refining), and mining ramp-up times continue to shape near-term availability. (International Energy Agency)

Deeper into Recyclability & Circularity (Repurposing)

- Lithium-ion (NMC/NCA): mature recycling methods exist (pyrometallurgy, hydrometallurgy); industry and academia (2024–2025) reported improvements in direct recycling and higher recovery rates in lab/pilot settings, but collection rates and industrial adoption are inconsistent (collection <10% in some regions). Economic viability depends on material prices and scale. (Green Li-ion)

- LFP: chemically simpler (no cobalt/nickel) but recovery of Lithium and phosphate at scale is still developing; recycling economics can be more challenging because LFP cathodes hold less high-value metals compared with NMC. Technologies are adapting to recover Lithium and reuse cell components. (Green Li-ion)

- Sodium-ion: less data at scale (early commercialization). In principle, sodium-based materials are abundant and less valuable, which reduces incentive for conventional metal-value recycling—so new business models (reuse, repurposing, design-for-recycling) and processes must be developed to ensure circularity. (IDTechEx)

- Author commentary: The trait that makes LFP and Na-ion so appealing is also what makes them less desirable for recycling.

Bottom line: recycling systems are evolving. High-value metals (Ni, Co) drive recycling economics today; shifting to LFP/Na-ion changes the economics and requires policy and technology adaptation to maintain circular supply.

The top recycling companies in North America are:

- Redwood Materials – www.redwoodmaterials.com

- Glencore (formerly Li-Cycle) – www.glencore.com

- American Battery Tech. – www.americanbatterytechnology.com

- Cirba Solutions (Retriev) – www.cirbasolutions.com

Circularity / Repurposing

More R&D is being conducted to explore and consider reusing (repurposing) used batteries. Virtually all recycling companies have repurposing as a profit center within their businesses, but startup companies and others are also coming to the forefront. It is not an easy proposition! Procuring, transporting the used batteries to the recycling site, disassembly, identifying usable cells and components, and then finding new buyers for the materials is difficult, but potentially lucrative.

- Ascend Elements – www.ascendelements.com

- RecycLiCo – www.recyclico.com

- KULR / Cirba – www.kulr.ai

- Princeton NuEnergy – www.pnecycle.com

- Green Li-ion – www.greenli-ion.com

Primary applications for repurposed batteries (Green li•ion)

- Stationary Energy Storage Systems: Used to store renewable energy (e.g., solar or wind) for grid support or peak shaving, extending battery life by 5–10 years in low-demand scenarios.

- Backup Power Systems: Deployed in critical infrastructure like hospitals, data centers, and telecommunications for uninterruptible power supplies during outages.

- Microgrids: Integrated into off-grid or resilient energy setups, such as solar PV + battery microgrids for remote communities or military bases, as seen in California Energy Commission-funded projects.

- Renewable Energy Integration: Paired with solar or wind farms to balance intermittent power generation and feed excess energy back to the grid.

SWOT Analyses

Lithium-ion (high-energy NMC/NCA)

- Strengths: highest energy density; mature manufacturing and supply chains for cells and packs; proven performance in EVs and consumer devices. (MarketsandMarkets)

- Weaknesses: reliance on limited minerals (Ni, Co, Li); higher intrinsic fire risk; cost volatility linked to critical minerals. (International Energy Agency)

- Opportunities: high-performance vehicles, energy-dense applications, and ongoing cost reductions through cell innovation and recycling improvements. (MarketsandMarkets)

- Threats: commodity supply shocks, regulatory and safety pressures, competition from LFP and Na-ion in certain segments.

LiFePO₄ (LFP)

- Strengths: excellent thermal safety, long cycle life, lower-cost inputs (iron/phosphate), strong for ESS and many EV segments. (Dataintelo)

- Weaknesses: lower energy density compared to NMC/NCA (heavier/larger for the same range), recycling economics less influenced by high-value metals. (Green Li-ion)

- Opportunities: continued adoption in EVs (budget/medium segments), grid storage, and markets where safety is critical. (solarctrl.com)

- Threats: potential displacement in high-range EVs and pressure if Na-ion reaches cost parity with similar safety.

Sodium-ion (Na-ion)

- Strengths: abundant raw materials (sodium), potentially the lowest raw-material cost, good intrinsic safety, and emerging manufacturability. (Reuters)

- Weaknesses: lower energy density than NMC (and often LFP), nascent recycling ecosystem, limited commercial track record at scale (2025). (IDTechEx)

- Opportunities: stationary storage, low-cost EV segments, geographic supply diversification for nations lacking Lithium resources. (Reuters)

- Threats: failure to meet promised cost/energy milestones, improvements in incumbent chemistry, and market conservatism slowing adoption.

Strategic Implications for OEMs and System Integrators

- Segment-fit strategy: Match chemistry to application — choose high-energy Li-Ions where range/weight is key; choose LFP/Na-ion for cost-sensitive or safety-critical systems. (Dataintelo)

- Supply-chain resilience: Diversify cathode sources and consider long-term contracts for critical precursors; evaluate LFP or Na-ion where regional supply risk for nickel/cobalt/Lithium is unacceptable and requires immediate attention to scale.

- Design for circularity: Invest in battery collection, design-for-disassembly, and support for direct/hydrometallurgical recycling — economics will shift as chemistries change. (Green Li-ion)

- Pilot sodium-ion where it fits: Monitor Na-ion commercialization and run pilot programs in non-critical or stationary segments to validate claims before large-scale adoption.

Risks & Open Questions (to monitor in 2025–2027)

- Will sodium-ion meet cost and energy targets at an industrial scale? (CATL rollout is a key point to watch. As they go, others will follow.)

- Will critical minerals supply/demand dynamics tighten or loosen in the short term (pricing and policy interventions)? International Energy Agency (IEA) and market signals should be monitored.

- Will cell manufacturing of all chemistries spread beyond what China is producing?

- If so, where?

- At what speed?

- How quickly will recycling technology and regulations develop to alter the economic calculus for each chemistry?

- For emerging technologies, will the investment community step up their speculation portfolio to quicken the pace in North America and beyond?

Selected References

- MarketsandMarkets — “Lithium-ion Battery Market Size” (2025 market estimates). (MarketsandMarkets)

- Industry/LFP market reports (various 2024–2025 analyses). (Dataintelo)

- CATL / Reuters coverage — CATL launches sodium-ion brand (Naxtra) and mass-production plans (2025). (Reuters)

- SodiumBatteryHub and IDTechEx market commentary on Na-ion commercialization outlooks (2025). (SodiumBatteryHub)

- Recycling & critical minerals analyses — CAS/industry recycling reports and IEA critical minerals outlook (2024–2025). (web.cas.org)

Final Thoughts and Recommendations

- For OEMs: consider adopting a mixed-chemistry strategy when feasible. Conduct thorough research to ensure the chemistry you select is optimal for your application. NMC/NCA, LFP, Na-ion, or potentially other emerging chemistries might be the best option, but maybe not.

- For stationary ESS and integrators: prioritize LFP today for safety and TCO; evaluate Na-ion pilots in cost-sensitive projects where energy density is less critical.

- For policy and recycling stakeholders: accelerate collection infrastructure and invest in direct and hydrometallurgical recycling to reduce reliance on virgin critical minerals.

- Adopt a robust partnership with the best pack assembler for your needs. Just as there are many cell types, chemistries, and unique cell attributes, virtually every pack assembler has a specialty, and one “size” does not fit all when it comes to pack assembler capabilities.

Addendum A – Cost Comparisons

2025 Battery Cost per kWh Comparison Analysis

Battery costs in 2025 continue to decline due to economies of scale, stabilized raw material prices, and manufacturing advancements, especially in China. Lithium-ion batteries (mainly NMC chemistry) average around $100 per kWh at the cell level, driven by higher nickel and cobalt content but benefiting from mature production. LiFePO4 (LFP) batteries, favored for stationary storage and cost-sensitive EVs, have dropped below $60 per kWh, making them 30-40% cheaper than NMC equivalents based on industry benchmarks. Sodium-ion (Na-ion) batteries, an emerging option using abundant sodium, show promising cost reductions with projections near $50 per kWh. However, real-world deployment remains limited, and claims of sub-$20 per kWh (e.g., from CATL) face scrutiny amid scaling challenges. These figures focus on cell-level costs for fair comparison; pack-level costs add 20-50% more.

The bar chart below visualizes these approximate 2025 cell costs for a direct side-by-side analysis.

Key Price/Cost Related Insights:

- Cost Leadership: LFP remains the leader for volume applications, but Sodium-Ion could challenge this if it hits $40/kWh at scale by late 2025.

- Trends: Expect a 10-20% price decrease across all technologies by 2026, with Sodium gaining ground in grid storage due to lower material volatility.

- Caveats: Prices are cell-level estimates from mid-2025 reports; actual prices vary by region, volume, and supply chain. For EVs, NMC possessing higher energy density justifies a premium.

Addendum B – Key Applications & Marketplaces

Much of the data available is driven by the EV marketplace. However, a deep dive into some key market segments is quite revealing for the Lithium battery usage: Source: (Grok-IEA or BloombergNEF)

Medical Devices

| Year | Total Medical Battery Units Produced | Lithium-Ion Share | Estimated Lithium Cells Produced | Key Notes/Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | ~200–220 million units (inferred from growth trends) | ~70% (140–154 million units) | ~140–200 million cells (assuming 1–1.5 cells per unit average) | Lithium-ion dominated with 60–70% market share; growth driven by portable diagnostics & implants. |

| 2024 | 250 million units | ~70% (175 million units) | ~175–250 million cells | Over 420 million portable devices shipped, many single-use or low-cell-count; market value $2.5 billion. |

| 2025 | ~260–270 million units (projected) | ~70–75% (182–203 million units) | ~182–300 million cells | CAGR of ~6.5%; rising demand for rechargeables in surgical tools (500-cycle life) and implants. |

Handheld and Industrial Controls

| Category | Est. Annual Cells Produced (2024) | Typical Cell Capacity | Key Drivers | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handheld Controls (remotes, controllers, etc.) | 200-500 million | 500-1,500 mAh (pouch/cylindrical) | Shift from disposable to rechargeable; smart home/IoT integration | Market reports on consumer electronics batteries |

| Automation Devices (industrial remotes, sensors) | 50-100 million | 100-1,000 mAh (coin/primary Li) | IIoT/remote monitoring; low-power wireless needs | IIoT device shipments; primary Li battery usage |

| Total for Segment | 250-600 million | – | – | Aggregated estimates of global Li-ion demand by application |

Solar and Off-Grid devices

| Year | Total Global Li-ion Production (GWh) | Estimated for Solar/Off-Grid (GWh) | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | ~1,000 | 40–70 | Utility-scale solar growth; off-grid in developing regions. |

| 2024 | ~1,100–1,200 | 50–80 | Record BESS additions; residential solar boom in California/Europe. |

| 2025 (projected) | ~1,500 | 80–120 | Policy incentives; China tenders exceed 210 GWh domestic storage. |

| 2030 (projected) | ~3,000–4,000 | 300–600 | Renewable integration targets: off-grid expansion to 1,095 GW cumulative. |

AMRs and AGVs

Estimated Annual Production of Lithium Battery Cells for AMRs and AGVs

Based on ~140,000 units shipped in 2025, with ~75% adopting Lithium-ion batteries (~105,000 units), and an average of 100 cells per pack:

- Total Cells Produced: ~10.5 million cells annually.

- Breakdown: ~8 million for AMRs, ~2.5 million for AGVs.

- Including replacements: Could rise to ~15 million cells (adding ~4.5 million for ~45,000 replacements).

This estimate aligns with the Lithium battery market for AGVs/AMRs, valued at ~USD 800-900 million in 2025 (part of the broader USD 1.57 billion market by 2031, growing at 10-12% CAGR). At an average cell cost of ~USD 5-10 (for industrial-grade LFP prismatic cells), this supports the volume.

| Category | Units (2025) | % Lithium-Ion | Avg. Cells/Pack | Total Cells (Millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMRs | 110,000 | 80% | 90 | 7.9 |

| AGVs | 30,000 | 60% | 120 | 2.2 |

| Total | 140,000 | 75% | 100 | 10.1 |

Truck and RV Start & Auxiliary (Non-EV)

Data on specific cell production volumes worldwide is limited, as most industry reports categorize Li-ion production into broader groups (for example, EVs account for about 70% of demand). Non-EV truck and RV uses are estimated to make up 1–3% of total Li-ion cell production based on market segmentation.

Total global Li-ion cell production reached approximately 2,500 GWh in 2023 and is expected to surpass 3,000 GWh in 2025. For the segment in question, annual cell production is conservatively estimated at 10–25 million cells in 2025, based on market sizes and average battery configurations (e.g., 4–8 cells per 12V pack), and adoption rates (5–15% in heavy-duty trucks initially; 20–30% for RV auxiliary systems).

This equates to approximately 5–15 GWh of capacity, a small part of the roughly 700 GWh used for non-EV automotive applications overall.

Humanoid Robotics (This is interesting)

Estimated Annual Number of Battery Cells

To derive cell counts, we use average pack specifications from leading humanoid models (e.g., Tesla Optimus, Figure 01, Boston Dynamics Atlas). A typical humanoid battery pack is 1.5–2.5 kWh, built from 40–100 cylindrical cells (3.6–4 V nominal per cell, 3–5 Ah capacity). Pouch or prismatic cells (fewer but larger) are alternatives in some designs. (Grok-AI search results)

| Model/Supplier Example | Avg. Pack Capacity | Typical Cell Type & Count | Est. Cells per Robot | Notes/Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tesla Optimus | 2.3 kWh | 21700 cylindrical (~4.8 Ah/cell) | ~63 cells | Vertical stack of two modules; modular for scalability. |

| Figure 01 | ~2 kWh | 18650/21700 mix (~3.5–5 Ah/cell) | 50–80 cells | High-density NMC 2–4 hr. runtime |

| Unitree H1 | 1.8 kWh | Cylindrical 18650 (~3.5 Ah/cell) | ~60 cells | Focus on lightweight (47 kg total robot weight). |

| Generic Average | 2 kWh | Mixed (40–100 cells/pack) | ~70 cells | 2025 market data assumes 3.7 V, 4 Ah cells. |

Addendum C – Discussion of Na-ion and Zero-Volt Discharge Capability

Overall, compared to Li-Ion and LiFePO4 (LFP), a major advantage of Sodium-ion (Na-ion) batteries is their ability to be discharged to 0V with almost no cell damage. With Na-ion, this is considered safe and reversible. This is one of the key practical benefits of Na-ion over lithium-ion and LFP.

Interestingly, Lithium Titanate Oxide (LTO) is a lithium chemistry that is also safe and can be reversed down to 0V.

Why Na-ion batteries tolerate 0 V well:

- No copper dissolution

- Most Na-ion cells use aluminum as the negative current collector, unlike copper in Li-ion cells. Copper dissolves above approximately 0.8–1 V vs. Li/LFP when over-discharged in Li-ion cells, causing irreversible damage. In contrast, aluminum does not dissolve or corrode significantly at low voltages, so even if the cell drops to 0 V, the current collector remains intact.

- Hard carbon anode behavior

- The most common anode in commercial Na-ion cells is hard carbon.

- Hard carbon can be fully de-sodiated (meaning “fully discharged,” with all sodium ions removed) without causing structural damage, and its potential plateau ends very close to 0 V.

- For many manufacturers (e.g., HiNa Battery, Farasis, CATL), their datasheets explicitly specify discharge to 0 V or 0.1 V.

- Cathode stability

- Common cathodes, including layered oxides, Prussian blue analogues, and polyanionic compounds, are stable when all sodium ions are fully removed. Prussian blue analogues (PBA), or “Prussian Blue-like,” as CATL refers to them, are especially tolerant and are routinely cycled down to 0 V in commercial products. Natron, now out of business, used PBA.